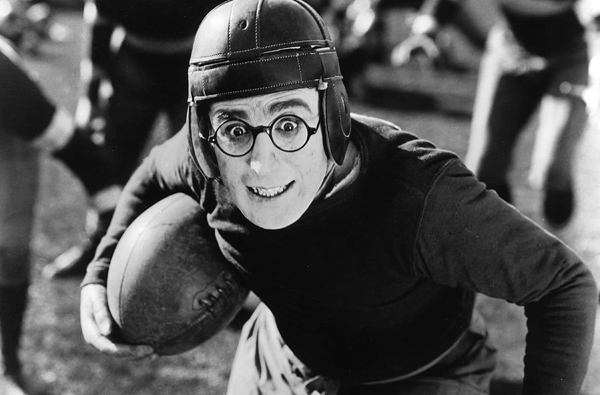

HAROLD LLOYD

Self-made man

SUNDAY, OCTOBER 15, 2017

We asked Stéphane Goudet, a film critic who runs Le Méliès movie theater in Montreuil, THREE QUESTIONS:

1) What sets apart the comedy of Harold Lloyd from that of Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton?

With Chaplin and Keaton, as noted by cinema historian Fabrice Revault d'Allonnes, there two figures, both historical and legendary, are tied to the history of the United States. Chaplin is the poor immigrant from old Europe, trying both to find his way on American soil and occupy a central place in its culture, meaning the cinema. Keaton, born in the United States, represents the pioneers, constantly tempted to continue his flight onward, toward the west. Harold Lloyd, on the other hand, is more integrated and more stable, but he must outdo himself to be recognized for his true worth. The "third genius,” as the documentary by Kevin Brownlow calls Lloyd, is thus a third American model: the self-made man, initially the everyman, just "him,” a man of the street, who succeeds in overcoming obstacles with a combination of ambition, cleverness and will, and ends up making his mark.

2) Tell us about a scene that fascinates you.

One cannot help but mention one of the most famous scenes of Harold Lloyd, where in Safety Last!, he is seen suspended in the void from the hands of a huge clock, hanging from a building. The scene is known for the rhythmic comedy of his vertical pursuit (especially in the obstacles encountered, including animals), for the virtuosity of the acrobatic actor, for his way of integrating speed and the urban modernity of the background, and for its clear symbolism. His ascent that suspends time is also a way for the hero to make good on his recent lie about his social status, to literally reach the top... of the company, and in doing so, be deserving of the woman he hoped to win over.

Whereas with Keaton, every impulse is thwarted by doubt, with Lloyd, lies become the truth, effort is productive and success is triumphant. But apart this iconic scene, the Lumière festivalgoers will also discover a thousand comical and poetic wonders, notably in Why Worry?, The Kid Brother or Speedy.

3) Why do you say that the legacy of Harold Lloyd can be found less in other comedians and more with Alfred Hitchcock?

We know that Alfred Hitchcock was influenced by the great figures of burlesque, especially Keaton and Lloyd, who helped him solve certain problems of rhythm, staging and mixing of genres, in Rich and Strange, for example. But Lloyd’s influence is not so much felt in the gags and jokes of Alfred Hitchcock as in their common taste for suspense and in the close connection established between laughter and fear. Their work is linked by a common motif: that of vertigo, of falling (Witness Hitchcock’s Blackmail, Rear Window, North by Northwest, or Vertigo). If Hitchcock defines this aspiration into the void as a deep source of anxiety, a universal and existential nightmare, Lloyd (especially in Never Weaken) makes us laugh, when he narrowly avoids the fall, which could be fatal, proving that all laughter is a victory in extremis, over death.

Rébecca Frasquet

> Harold Lloyd cine-concerts at the Auditorium of Lyon

The Kid Brother by Ted Wilde and J.A. Howe (1926, 82 min)

By the National Orchestra of Lyon conducted by Carl Davis

Wednesday, October 18 at 8pm

At the Auditorium of Lyon

Monte là-dessus by Sam Taylor and Fred Newmeyer (1923, 80 min)

Musical accompaniment on the organ by Samuel Liégeon

Sunday, October 22 at 11am

At the Auditorium of Lyon